Control Unit & Instruction Register

Basics Primer

The Control Unit (CU) is what ties all of the modules in a CPU together. It does not process or store data, but acts as a central hub for directing the use of other parts of the computer. It converts the instructions fetched into the CPU into a series of control signals that activate other parts of the computer. The design and complexity of a CU can vary greatly between different CPUs, but its fundamental purpose remains the same: to serve as the command and control center for the CPU's operations.

The Instruction Register is a special register within the CPU that holds the instruction currently being executed/decoded. When an instruction is fetched from memory, it is placed into the IR, the CU then reads this instruction and determines what action the CPU needs to take. Part of the instruction usually includes an opcode (operation code) which specifies the operation to be performed, such as adding two numbers or loading data from memory. The rest of the instruction may include addresses or data that are necessary for the operation.

The Von Neumann architecture is a foundational design model for computer architecture that is still widely used. It is characterized by the storage of both program instructions and data in the same memory space. This design contrasts with the Harvard architecture, which uses separate memory spaces for data and instructions.

In the Von Neumann model, instructions and data are fetched from the same memory and then executed by the CPU. This architecture typically involves a sequential process of fetching an instruction, decoding it, and then executing it, which is known as the fetch-and-execute cycle.

My CPU, being based on the SAPs is an example of a computer that follows the Von Neumann architecture.

The Von Neumann Fetch-and-Execute Cycle

Here’s a simplified outline of the steps in the Fetch-and-Execute cycle in a basic Von Neumann architecture:

Note: While the term “fetch-and-execute cycle” is used to describe the sequence of operations a CPU performs to execute an instruction, it is important to note that in this context, “cycle” does not equate to a single clock cycle. Each part of this process; fetching, decoding, and executing; can span multiple clock cycles. Therefore, the term “cycle” here should be understood as a sequence of steps or a process, rather than a measure of time tied to the CPU’s clock.

1- Fetch

The CPU first retrieves the address of the instruction that is about to be executed from the Program Counter(PC). This address is typically moved to the Memory Address Register (MAR) from the PC. Subsequently, the instruction at that address(The address in the MAR) is transferred from memory to the Instruction Register (IR). Immediately after moving the instruction’s address from the PC to the MAR, the PC increments by one to point to the next instruction address.

2- Decode

The Control Unit (CU) decodes the instruction stored in the IR by interpreting the opcode to determine the operation to be performed. Additionally, the CU may extract operand addresses or immediate values from the instruction. It’s important to note that the decoding process varies depending on the complexity and design of the CU and the instruction set architecture of the CPU.

3- Execute

To now execute the fetched and decoded instruction, the CU issues control signals to relevant parts of the CPU to carry out the instruction. This phase can involve a variety of operations, such as directing the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) to perform a computation, moving data between registers, or handling interactions with memory. The execution process is closely tied to the specifics of the instruction set and the architecture of the CPU.

The Instruction register

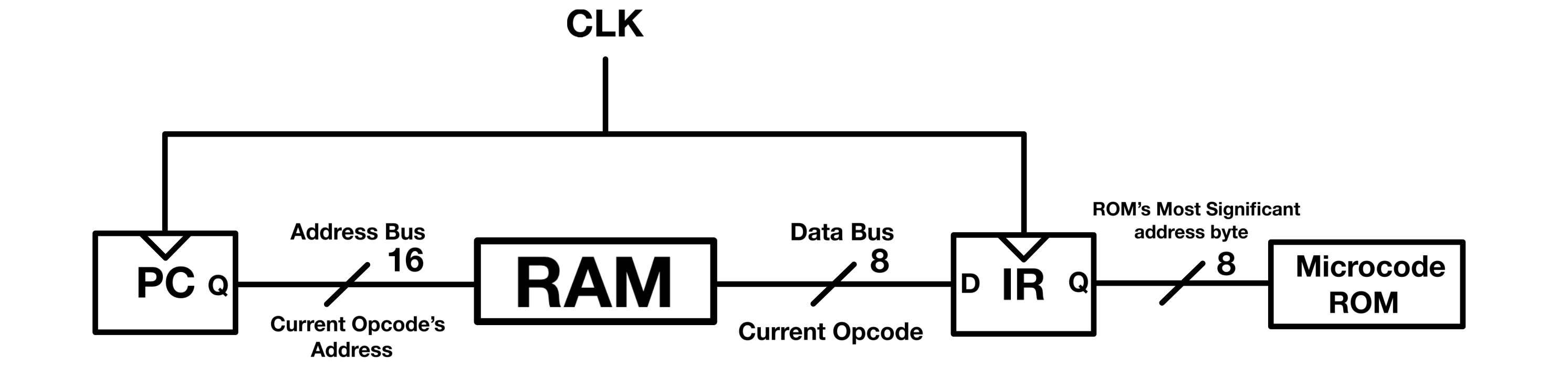

The instruction register is extremely simple. As mentioned in the primer, it holds the instruction currently being executed. On my build, the IR’s output is permanently tied to the Microcode ROM and nothing else. This necessitate a subtle clarification that needs to be made regarding what an instruction is in general.

Difference Between an Opcode and an Instruction

An instruction is simply a complete command that tells the CPU what to do. It consists of an opcode and, often, additional information like operand addresses or immediate values. The opcode, or operation code, is part of the instruction that specifies the operation to be performed.

In modern CPUs, an instruction typically contains other information such as addressing modes, and condition codes; which for the sake of this discussion can all be considered part of the opcode.

For example, consider an instruction like ADD A, B. Here, ADD is the opcode that tells the CPU to perform an addition operation, while A and B are operands, specifying where the data for the operation comes from or goes to.

In binary form(Machine code), the instruction might look something like 0b00011011 , where a part of the binary code (e.g., 0b0001) represents the opcode for ADD, and the rest (0b1011) indicates the operands A and B.

Not all instructions require operands. Some instructions, like NOP (no operation) or HLT (halt), consist only of an opcode. For example, NOP might be represented as 0b0010 in binary form, with no additional operand information needed.

Instructions Encoding On My CPU

In my design I do not structurally split the instruction into an opcode and operand. Each instruction is a unique encoding/address that the microcode ROM interprets to perform the necessary operations.

This means that operand handling in my design is indirect: The PC increments by 1 to fetch the operand in memory, unlike the direct operand used in traditional models.

To understand my encoding, let’s consider the LDA(Loads register A with the content at a memory address) instruction in Ben Eater’s SAP-1 and in my instruction set.

How we go from a strings like “ADD” and “LDA” to a number is clarified in the “Assembly” post. For now; it is sufficient to know that these instructions are written in what is called an “Assembler”. The assembler is what translates the words to machine code.

SAP-1’s LDA

As a reminder the SAP-1 is an 8-bit CPU. It has 16 bytes of RAM and therefore, a 4-bit PC and a 4-bit MAR. Though the SAP-1 has an 8-bit IR, only the 4 MSB of the IR’s output are connected to the micro-code ROM. This way, the most significant 4 bits serve as the opcode, and the remaining four bits as the operand. The opcode for LDA is programmed with 0b0001 in the original Ben Eater SAP-1.

- For an LDA instruction to load data from memory address

0b1010, the encoding would be0b00011010(LDA0b1010). Here,0b0001is the opcode for LDA, and0b1010is the operand specifying the memory address. - Execution Process: The opcode (

0b0001) informs the microcode ROM to initiate a load operation. The operand (0b1010) is used to set the Memory Address Register directly, pointing to the memory location whose data will be loaded into register A.

My LDA

Instead of a split between opcode and operand, each instruction has a unique, arbitrary encoding that the microcode ROM interprets as a whole. In the current version of the my micro-code ROM, the LDA(MOV $A, [address]) instruction is located at address 0b10100101 or 0xA5.

- For an LDA instruction to load data from memory address

0b1010, the encoding would be0b10100010(MOV $A,0b0000000000001010). - Execution Process: The instruction itself leads to a series of actions necessary to fetch the operand. In this case, the Program Counter increments thrice (Once to load MOV $A, and twice to load the lower and upper byte of the address respectively).

The Microcode ROM

The Microcode ROM provides a low-level control mechanism for defining the behavior of the CPU during the execution of instructions. Specifically; it contains a set of predefined values that serve as control signals through the ROM’s output pins for each step of every instruction’s execution. My CPU’s microcode ROM contains the following inputs:

- The content of the Instruction Register(8 bits)

- The content of the Flags Register(4 bits)

- The Interrupt Inhibit and Interrupt Request Flags(2 bits)

- The content of the Microcode Step Counter(4 bits)

Totaling in an 18-bit input word. Every single one of the $2^{18} (262144)$ addresses has a known content.

Flags

Flags are indicators that signal various conditions that may occur during the execution of instructions. The state of the flags influences the control signals generated by the Microcode ROM, affecting the flow of program execution and decision-making processes within the CPU.

Types of Flags on my CPU

ALU Flags

ALU flags are often used for conditional branching in programs, where the flow of execution depends on the results of previous operations. All of my ALU flags are described in more details in the “ALU & Flags” post.

- Zero Flag (Z): Indicates whether the result of an operation is zero.

- Overflow Flag (O): Indicates whether an arithmetic operation results in a value too large to be represented in the number of bits used.

- Negative(Sign) Flag (N): Indicates whether the result of an operation is positive or negative (usually the most significant bit of the result).

- Carry Flag (C): Indicates whether an arithmetic operation results in a carry out or borrow into the most significant bit.

Interrupt Flags:

More information about the interrupt flags and interrupt mechanism will be made available in a future “Interrupts” post.

- II (Interrupt Inhibit, A9): Indicates whether interrupts are currently inhibited.

- IR (Interrupt Request, A8): Signals whether an interrupt request has been made.

Micro Steps

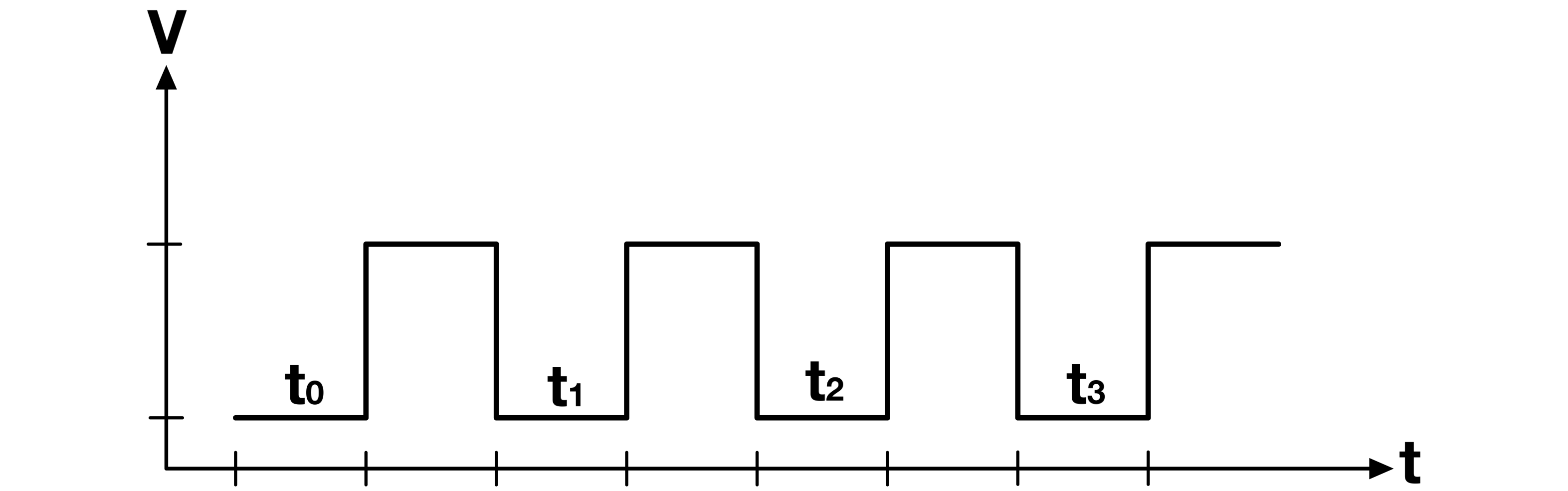

Micro-steps or micro operations, are individual stages within the execution of a single instruction. Each micro-step corresponds to a specific set of control lines upon which the remaining micro steps for the instruction depend. In my CPU, micro steps occur on the low phase of the clock cycle.

The Micro-Step Counter

The micro step counter is a register that tracks the current step in the execution of an instruction. It ensures that the CPU executes each step in the correct order. While data is latched into parts of the CPU at the rising edge of the clock, the control lines necessary for this latching are set during the low phase of the clock, at each increment of the micro-step counter. In other words the micro-step counter increments on the falling edge of the clock and asserts the necessary control lines at every increment.

Clock Behavior:

- On the Rising Edge of the Clock: The current micro-step’s actions are completed, and the system prepares for the transition to the next micro-step. The control signals activated during this micro-step remain in effect until the next falling edge.

- On the Falling Edge of the Clock: The micro-step counter increments, moving the execution to the next set of control signals in the Microcode ROM. This increment triggers the appropriate control lines for the next phase of instruction execution.

For the sake of clarity, let’s observe the micro-steps involved in the SAP-1’s LDA in more details.

Note: In most CPU architectures based on the Von Neumann model, including the SAP-1, the fetch and decode steps are similar for every instruction due to the standardized and sequential nature of these processes. The fetch step is always about retrieving the next instruction from memory, while the decode step consistently involves interpreting the opcode from the fetched instruction to determine the type of operation to be performed.

Base Assumption

- Let’s assume that the Program Counter is initially at address

0b0000. - It is also important to note that since all instructions begin with a fetch and decode step, and provided the micro-step counter is at 0, the Microcode ROM would output Fetch control lines no matter the opcode currently in the instruction register.

And finally, let’s assume that the program is stored in RAM as follows:

RAM Address Content 0b0000 0b00011000 0b0001 xxxx 0b0010 xxxx 0b0011 xxxx 0b0100 xxxx 0b0101 xxxx 0b0110 xxxx 0b0111 xxxx 0b1000 0b11011000

xxxx = Don’t care.

Below are the control lines involved in the LDA instruction:

- MI (MAR In): Loads the Memory address register on the next clock edge.

- CO (Program Counter Out): Outputs the content of the Program Counter to the bus.

- RO (RAM Out): Outputs the content of the RAM at the specified address to the bus.

- II (Instruction Register In): Loads the Instruction Register on the next clock edge with the content at tits input.

- CE (Counter Enable): Increments the Program Counter by one on the next clock edge.

- IO (Instruction Register Out): Outputs the content of the Instruction Register to the bus.

- AI (A Register In): Loads data into the A register.

This time, let’s consider LDA 0b1000(Load register A with content at memory address 8).

1- Fetch

At micro-step 0: PC = 0b0000 MAR = xxxx

From the falling edge of the clock to the end of the LOW phase:

MI and CO are asserted at the output of the micro-code ROM. Meaning that the Program Counter’s content(0b0000) is available at the input of the Memory Address Register.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

The MAR **is **latched **with 0b0000.

At micro-step 1: PC = 0b0000 MAR = 0b0000

From the falling edge of the clock to the end of the LOW phase:

RO, II, **and **CE are asserted at the output of the micro-code ROM. The RAM’s content (0b00011000) at address 0b0000 is now on the data bus, and the instruction register is ready to be latched.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

The PC is increments by one (via CE) to point to the following instruction, and the instruction register is latched with 0b00011000.

2- Execute

At micro-step 2: PC = 0b0001 MAR = 0b0000

From the falling edge of the clock to the end of the LOW phase:

At this point, the microcode ROM “sees” micro step 2 of LDA 0b0001 at its input. And since it is programmed for every possible input; it “knows” what to do next. In this specific case, the microcode ROM asserts the IO and MI control lines presenting the least significant four bits of the instruction register(0b1000) to the MAR’s input.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

The MAR **is **latched **with 0b1000.

At micro-step 3: PC = 0b0001 MAR = 0b0001

From the falling edge of the clock to the end of the LOW phase:

Now the microcode ROM “sees” step 3 of LDA(0b0001) at its input. RO and AI are asserted; placing the content of RAM(0b11011000) at address 0b1000 to the bus.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

Register A is loaded with 0b11011000, marking the end of the program.

The HLT instruction could have been added to the program after this step to stop the clock after execution.

The Fetch-And-Execute Cycle On My CPU

As mentioned in the RAM module, my build does not use a MAR, because it has a dedicated memory/system bus. This means that, the content of the Program Counter can be directly presented to the RAM’s input pins without any intermediary steps.

In other words, the instruction fetching is done in one cycle.

Beside each instruction being specific to my ISA; the Execute steps logic is the same as that of the SAP-1.

Now, let’s observe the micro-steps involved in my CPU’s LDA (MOV $A, [address]) in more details.

Base Assumption

Let’s assume that the program is stored in RAM as follows:

RAM Address Content 0b0000000000000000 or 0x0000 0b10100010 or 0x00A2 0b0000000000000001 or 0x0001 0b00001000 or 0x0008 0b0000000000000010 or 0x0002 0b00000000 or 0x0000 0b0000000000000011 or 0x0003 xxxxxxxx 0b0000000000000100 or 0x0004 xxxxxxxx 0b0000000000000101 or 0x0005 xxxxxxxx 0b0000000000000110 or 0x0006 xxxxxxxx 0b0000000000000111 or 0x0007 xxxxxxxx 0b0000000000001000 or 0x0008 0b11011000 or 0x00D8

xxxxxxxx = Don’t care.

- All other assumptions are similar to those made in the SAP-1 example.

Below are the control lines involved in the LDA instruction:

- PCE Program Counter Enable: Enables PC’s content to the address bus.

- PCC Program Counter Count Up: Increments PC by 1.

- ME Enables memory output to the data bus.

- BRlW Bridge Lower Write: Writes the content on the data bus to the lower byte of the transfer register.

- BRhW Bridge Higher/Upper Write: Writes the content on the data bus to the upper byte of the transfer register.

- BRE Bridge Enable: Enables the address bus to the transfer register’s input.

- AW Register A Write: Loads data into the A register.

- IR_in Instruction register in.

This time, let’s consider LDA 0b00001000(Load register A with content at memory address 8).

1- Fetch

At micro-step 0: PC = 0x0000

From the falling edge of the clock to the end of the LOW phase:

PCE, ME, IR_in and PCC are asserted at the output of the micro-code ROM. Meaning that the Program Counter’s content(0x0000) is available at the input of the RAM. Simultaneously; the RAM’s content(0b10100010) at 0x0000 is presented to the Instruction Register through the data bus.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

The LDA instruction(0b10100010) **is **latched **into the IR, and the PC increments by 1.

2- Execute

At micro-step 1: PC = 0x0001

From the falling edge of the clock to the end of the LOW phase:

PCE, ME, BRlW and PCC are asserted at the output of the micro-code ROM. Meaning that the Program Counter’s content(0x0001) is available at the input of the RAM. Simultaneously; the RAM’s content(0b00001000) at 0x0001, which is the lower byte of the LDA operand is presented to the low byte of the Transfer Register through the data bus.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

The lower byte of the Transfer Register **is **latched **with 0b00001000, and the PC increments by 1.

At micro-step 2: PC = 0x0002

From the falling edge of the clock to the end of the LOW phase:

PCE, ME, and BRhW are asserted at the output of the micro-code ROM. Meaning that the Program Counter’s content(0x0002) is available at the input of the RAM. Simultaneously; the RAM’s content(0b00000000) at 0x0002, which is the upper byte of the LDA operand is presented to the upper byte of the Transfer Register through the data bus.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

The upper byte of the Transfer Register **is **latched **with 0b00000000, and the PC increments by 1.

At micro-step 3: PC = 0x0003

BRE, ME, AW and PCC are asserted at the output of the micro-code ROM. Meaning that the Transfer Register’s content(0b0000000000001000) is available at the input of the RAM. Simultaneously; the RAM’s content(0b11011000) at 0x0003, is presented to the input of the A register through the data bus.

From the rising edge of the clock to the end of the HIGH phase:

Register A **is **latched **with 0b11011000, and the PC increments by 1.

At micro-step 4: PC = 0x0004

At the falling edge of the clock:

ScR is asserted at the output of the micro-code ROM, resetting the Step Counter.

Implementation

Control lines involved(6):

ROM 0

| Control Signal | Description |

|---|---|

| _CLKW | Clock speed select |

| _DW | D Register (General purpose register 4) Write |

| _BW | B Register (General purpose register 2) Write |

| H_cin | Shift register carry in |

| _HC | Shift register clear/reset |

| ZS | ALU select (0: 382 ALU; 1: 194-shift register) |

| Z2 | ALU control_2 |

| Z1 | ALU control_1 |

| _FW | Flag register write/in |

| IR_in | Instruction register in |

| TI | Toggle interrupt (Sets interrupt to its opposite state) |

| _OS | OLED select (D/C# Data by default, command when asserted) |

| OR | OLED data (Read/_Write Write by default, read when asserted) |

| _OE | OLED enable (Read/write is enabled when pulled high) |

| _OC | OLED clear |

ROM 1

| Control Signal | Description |

|---|---|

| EX | Extra (Extra/Unused control line) |

| SdM | Segmented display mode (Signed/_Unsigned) |

| Z0 | ALU control_0 |

| _ScR | Step counter reset to 0 |

| BRlW | Transfer Register lower byte write |

| _PChE | Program counter upper byte enable |

| _PClE | Program counter lower byte enable |

| _GE | G Register (General purpose register 6) enable |

| GW | G Register (General purpose register 6) Write |

| EX 2 | Extra line 2 |

| _PSE | Port selector enable |

| _PSW | Port selector write |

| HLT | Clock halt/stop |

| SPW | Stack pointer load |

| SPD | Stack pointer count direction (_up/down) |

| _SPC | Stack pointer count enable |

ROM 2

| Control Signal | Description |

|---|---|

| _SPE | Stack pointer word (16-bits) enable |

| BRhW | Transfer Register upper byte write |

| _MW | Memory write |

| ZW | Accumulator write |

| _BRE | Transfer Register word (16-bits) enable |

| _PCE | Program counter word (16-bits) enable |

| PCC | Program counter count up |

| _PCW | Program counter write/in (Jump) |

| _PS | Port select in |

| WR_2 | Write decoder A2 (74HCT238) |

| WR_1 | Write decoder A1 (74HCT238) |

| WR_0 | Write decoder A0 (74HCT238) |

| RD_3 | Read decoder A3 (74HCT154) |

| RD_2 | Read decoder A2 (74HCT154) |

| RD_1 | Read decoder A1 (74HCT154) |

| RD_0 | Read decoder A0 (74HCT154) |

Micro-Code ROM

The micro-code ROM consists of three ST M27C4002 EPROMs(which I collectively refer to as the micro-code ROM), each having a 16-Bit output. This provides 48 control lines coming directly form the ROM. To have even more control lines; the four most significant output bits of the ROM are multiplexed to output a set of Enable/Output and Write control lines.

Since only one component can output to the data bus at a time, most of the data-bus-enable control lines are implemented as the output of 4-to-16 decoder. This way, instead of having a control line dedicated to each of the 12 enable lines coming from the decoder; only four control lines are used to select the decoder’s output. Additionally, five control lines are also implemented using a 3-to-1 multiplexer.

With the current configuration, I have 7 spare control lines from both multiplexers; and two lines directly from the microcode ROM, which I can use in the future if needed.

In total, I have 48 + 16 + 8 = 72 control lines.

NOTE: I initially used the TMS27PC240-12(which has the same pinout as the M27C4002) as my control ROM, but for reasons that ignore, the ROM malfunctioned(froze the entire CPU) every time the Interrupt-Inhibit flag was asserted. I have nine of these ROMs, which all caused the same issue.

Micro-Step Counter, Instruction Register and Hard Reset

Each instruction can have up to 16 micro operations. The micro step counter is implemented with a single 74HCT161 counter. The advantage of the 161 is that it has an asynchronous reset, meaning that the content of the register can be reset independently of the clock. This is very convenient for two main reasons:

Not all instructions need the 16 steps available; therefore the Step Counter dynamically points back to zero right after the last micro operation of every instruction. To achieve this; every instruction is coded to end with a ScR(Step Counter Reset) assertion. Because the reset feature of the 161 is asynchronous(Independent of the clock); as soon as ScR is asserted during the low phase of the clock, the Step Counter immediately resets back to zero and points the micro code ROM to the fetch micro step of the current instruction.

When starting up the CPU, the clock state and all registers contents are undetermined. To bring the CPU to a known state where programs can start being fetched; a manual push button is used to reset the Step Counter(and the Program Counter) at power up. The asynchronous reset allows this hard reset to be done without depending on the clock.

The instruction Register is a 74HCT273 8-bit register with asynchronous reset as well. The hard reset pin is also connected to the IR’s reset pin, which means that when pressing the RST button, the micro code ROM points to step 0 of the instruction at location 0x00.

Reset Vector(Soft Reset)

At address 0x00 of the micro code ROM, no matter what flags are active, the Soft Reset instruction RST, jumps to address 0xC000(0b11000000_00000000) of memory, which is the start address of the bootloader EPROM, where code can be more flexibly written, as the OS ROM is electrically erasable.

A reset instruction/vector is implemented at address 0x00, of the micro code ROM. Below are its micro operations:

$t_0$: Writes zero into accumulator.(The OLED reset line is asserted from here to t_3)

$t_1$: Writes zero into accumulator.

$t_2$: Writes 0 into register A, Transfer Register, and Instruction Register(Not really necessary as the IR is hard reset to 0 already).

$t_3$: Writes 0 into register C, Stack Pointer, and Flags Register.

$t_4$: Writes zero into temporary Segmented Display Register, decrements Stack Pointer’s content by one, from 0x0000 to 0xFFFF.

$t_5$: Writes 0 into segmented display register, and registers B, D, and E; and 0b10000000 into shift register.

$t_6$ to $t_9$: Write 0b11000000(0xC0) into high byte of Transfer Register.

$t_{10}$: Writes 0xC000 into PC. Now PC points to the start of the boot loader ROM.

$t_{11}$: Inhibits Interrupt

$t_{12}$ to $t_{14}$: All control lines of the micro code ROM get deactivated(Active LOW lines are set to 1 and Active HIGH lines are set to 0) throughout these unused steps. This way even if the instruction loaded at $t_{15}$ has micro operations in the range of $t_{12}$ to $t_{14}$, it will only be loaded when the Step Counter is about to reset, avoiding parts of the instruction to be performed midway through the soft reset.

$t_{15}$: Loads the instruction register with the instruction at 0xC000 (First address of bootloader ROM).

The reason why both step 0 and 1 load zero into the accumulator is because the clock state is unknown when the CPU powers up. If the clock is LOW at the instant when the CPU goes on, 0b00000000 will be written into the accumulator at the rising edge of the clock. But if the clock is HIGH at the instant when the CPU goes on, the micro-operation step counter would automatically go to step two(t_1) at the falling edge; but since t_1 does the same action as t_0 this would not pose a problem.

ICs

1x 74HCT273 Octal D-Type Flip-Flops With Clear (Digikey, Datasheet)

2x 74HCT161, Synchronous 4-Bit Binary Counters, (Digikey, Datasheet)

1x 74HCT14 Hex Schmitt-Trigger Inverters (Digikey, Datasheet)(Shared with Permanent Clock)

1x 74HCT02 Quadruple 2-Input Positive-NOR Gates (Digikey, Datasheet) (Shared with Permanent Clock)

1x 74HCT00 Quad 2 Input NAND Gate (Jameco, Datasheet) (Shared with Permanent Clock)

1x 74HCT154 4-TO-16 INVERTING DECODER, (Jameco, Datasheet)

CMOS UV TMS27C240 EEPROM 4MBit (256K x 16) (Jameco, Datasheet)

1x 74HCT238 3-TO-8 NON_INVERTING DECODER, (Digikey, Datasheet)

«««««««««« Previous Post: Program Counter & Stack Pointer

Next Post: Assembly »»»»»»»»»»

Updated: