Permanent Clock

The frequency of the debugging clock is limited to a few kilohertz with a variable resistor. This limitation means that I didn’t have to deal with timing instability issues that become more pronounced at higher frequencies. However, the permanent clock necessitates a more cautious approach to avoid any potential timing issues that could arise from pushing the hardware to its limits. Additionally, I wanted to have the ability to programmatically switch to lower clock speeds in case some programs ran too fast(Ex: animations on the OLED display); therefore, I made a simple programmable clock speed module that allows for division into eight different speeds using a counter and a multiplexer.

Clock Speed Calculation

Propagation Delays and Critical Path

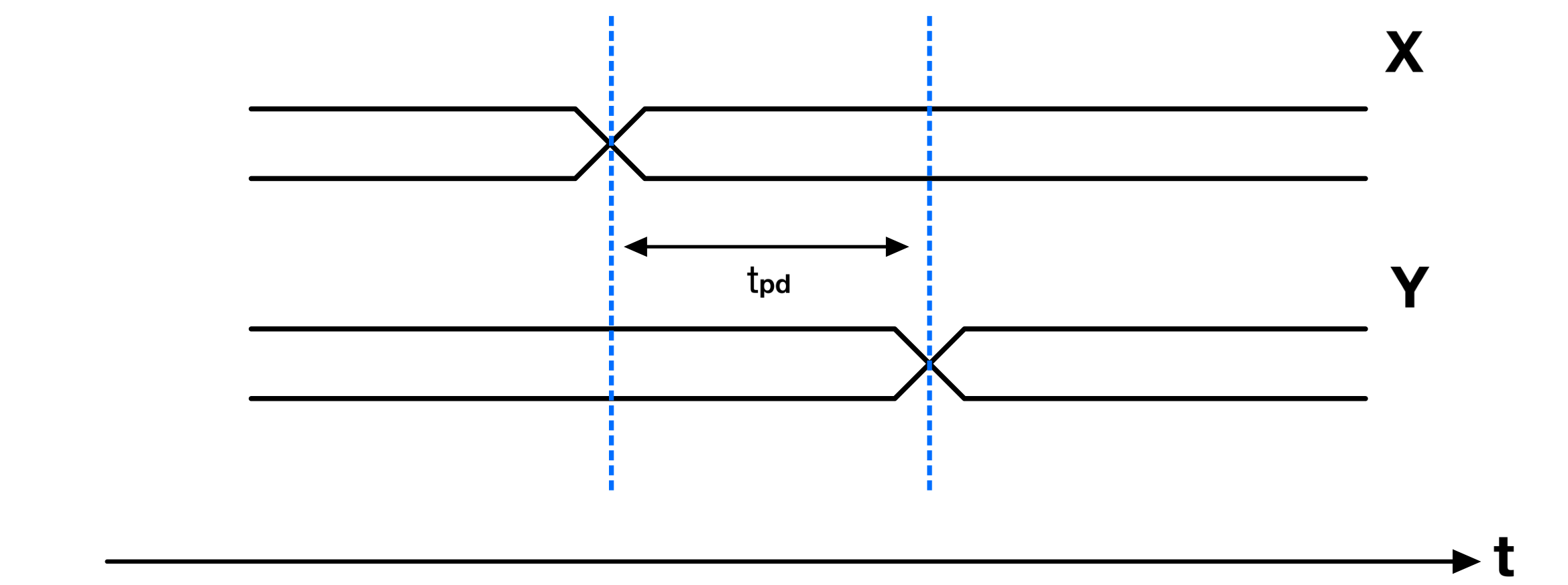

Propagation Delay

The propagation delay ($t_{pd}$) of a digital circuit is the maximum time taken for a change in input to stably reflect at the output. Different kinds of propagation delays arise due to the inherent physical characteristics of the circuit components, such as the capacitive and resistive properties of transistors and the interconnections between them. They vary from component to component and are influenced by factors like temperature, supply voltage, and manufacturing variances.

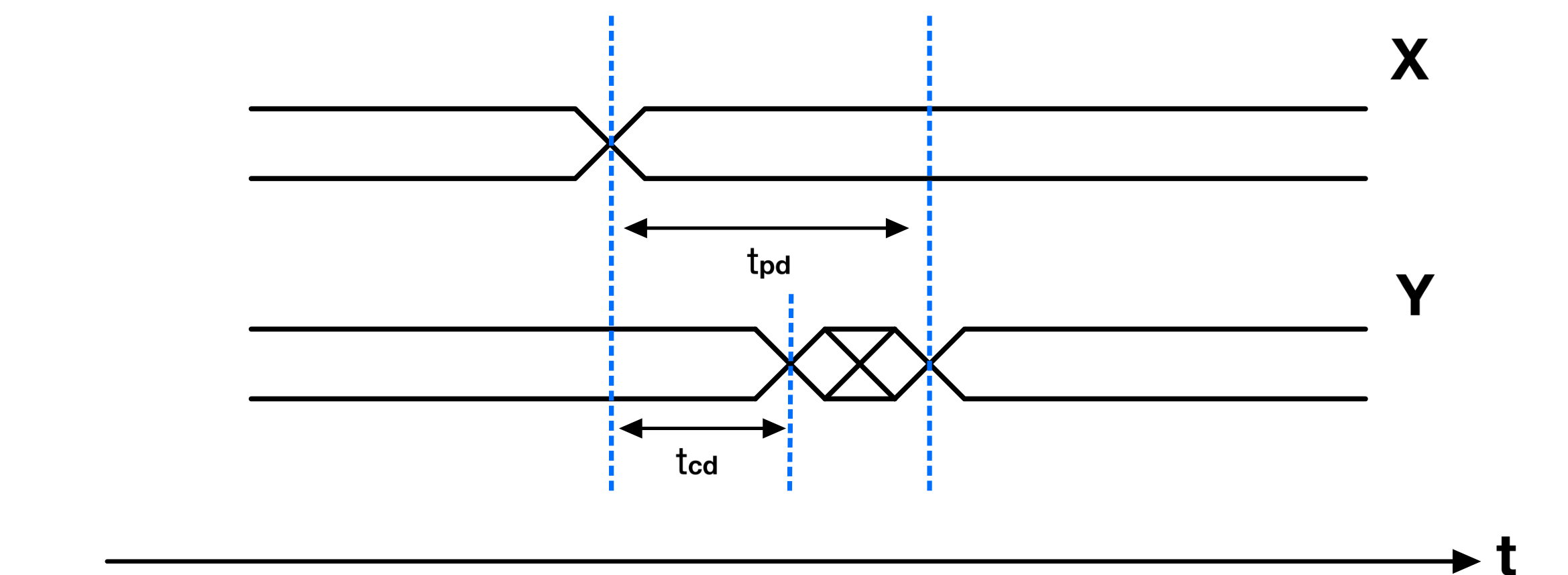

It’s worth noting that there’s another type of delay called contamination delay, which refers to the minimum time it takes for a change at the input of a gate to begin affecting the output. However, for the purpose of this post, I will consider contamination delays as inexistent.

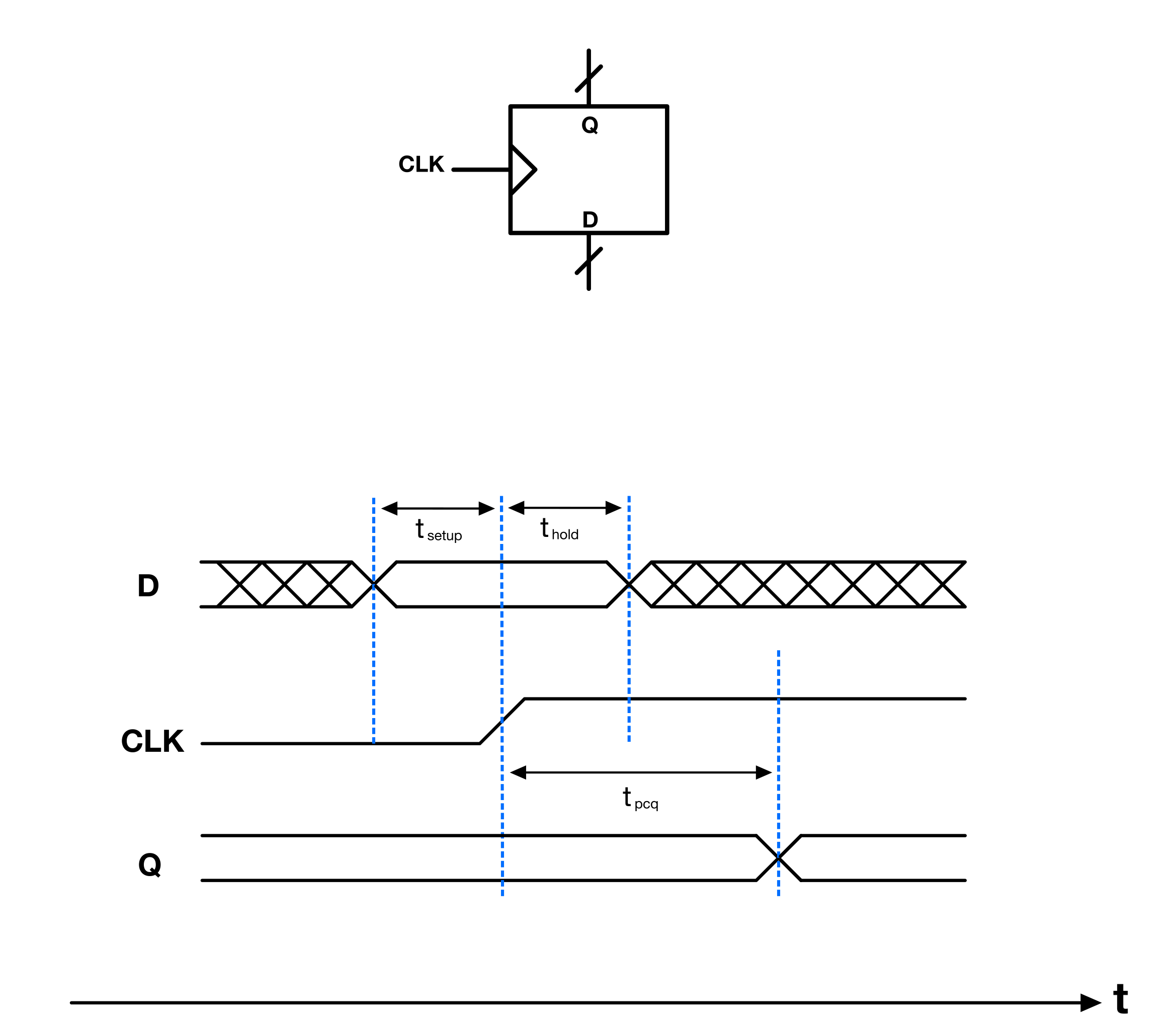

In the context of synchronous sequential circuits(like a flip flop), the clock-to-Q propagation delay ($t_{pcq}$) refers to the time from the clock’s active edge until the output stabilizes to its new state.

A synchronous sequential circuit has a somewhat strict definition; however for this discussion, it’s sufficient to view them as systems where all registers are synchronized to a common clock signal.

Setup and Hold Time

In addition to ($t_{pcq}$), there are two other important timing considerations: setup time ($t_{setup}$) and hold time ($t_{hold}$):

- The setup time ($t_{setup}$) is the minimum time before the clock edge by which the input data must remain stable to be correctly captured by a circuit.

- The hold time ($t_{hold}$) is the minimum duration for which the input data must remain stable after the clock edge.

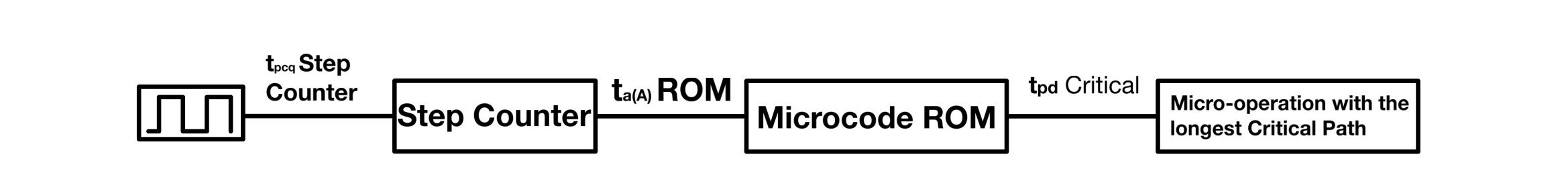

Critical Path

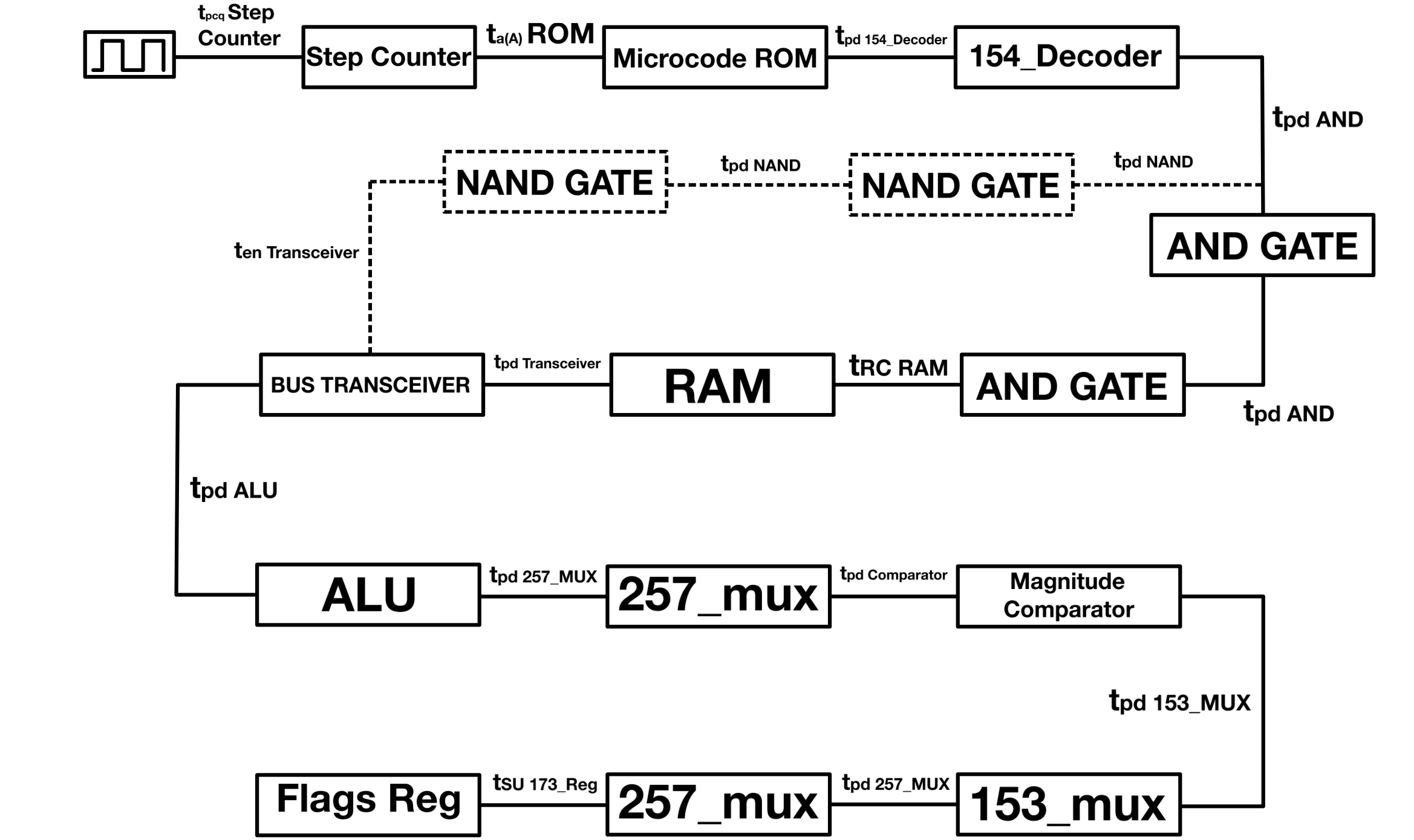

The critical path in a digital circuit is the sequence of components that results in the longest delay from one point to another. Trying to make the circuit work faster than the critical path allows may end up with errors because some parts of the circuit won’t be ready in time for the next set of operations. The critical path of the CPU contains the following:

I set out to use the timing constraints of the chips in my build’s critical path at 4.5V and 25 degrees Celsius. However, some of the datasheets for the chips I used provide switching information only for 5V.

Generally speaking, lower temperatures reduce the resistance of semiconductor materials, which in turn leads to an increase in electron mobility and consequently, a higher speed.

Also, increasing the supply voltage(Within the chip limit of course👀) for a chip typically results in increased speed as well. This happens because a higher voltage reduces the time it takes to charge and discharge the capacitive elements within the chip, leading to faster switching speeds for transistors.

The voltage at my rails is somewhere around 4.90V; which is higher than the 4.5V I consider for timing. Also, the CPU is always going to be indoor at room temperature(much less than 25 degrees Celsius).

All of that being considered, the maximum timing requirements at 4.5V/25°C should be enough to compensate for the lack of 4.5V data in some datasheets, as the higher rail voltage and lower operating temperature in my setup ensure that the chips will operate well within their specified limits at 5V.

The HIGH phase of the clock is just to latch data prepared during the LOW phase; therefore the critical path for the HIGH phase is pretty straightforward: It is the chip with longest $t_{pcq}$ latched during the HIGH phase. The register with the highest $t_{pcq}$ is the 74HCT194 shift reg, with a $t_{pcq}$ max of 37ns.

Therefore $t_{pcq}$(HIGH) = 37ns.

The LOW phase on the other hand has a critical path depending on my instructions implementation. More specifically, the micro operation in all instructions that requires the most time to be completed.

The micro operations that take the most time are those that must:

- Access memory

- Output the memory content and input it to the ALU

- Input the result from the ALU to the zero detector

- Input the zero detector’s result to the flags mux

- Then write the content at the output of the flags mux to the Flags Register.

Going by the max propagation delay of the chips I’ve used; the enable signal of the RAM’s bus transceiver arrives to the transceiver $1ns$ after the RAM content is presented to input of the transceiver.

Below are the time delays for every elements on the low phase’s critical path(Excluding the AND gates and the RAM chip):

74HCT161 Counter

$t_{pcq}$(4.5V): max = 39ns

TSM27C240 Control ROM

$t_{a(A)}$ Access time from address and ta(E) Access time from chip enable(5V) = max = 120ns

74HCT257 4-to-16 DECODER

$t_{pHL}$ and $t_{pLH}$(4.5V): max = 35ns

74HCT08 AND

$t_{pHL}$ and $t_{pLH}$(5V): typ = 11ns; max = 18ns

UM61512A-15 RAM

$t_{RC}$ (5V) = 15ns

74HCT00 NAND

$t_{pHL}$ and $t_{pLH}$(5V): typ =18ns; max = 23ns

74HCT245 Transceiver

$t_p$(4.5V): max = 26ns

$t_{en}$(4.5V) Output enable to output: max = 32ns

74LS382 ALU

$t_{pLH}$(5V): typ = 20 ns; max = 30ns

$t_{pHL}$(5V): typ = 15 ns; max = 23ns

Using 30ns

74HCT257 2-to-1 MUX

$t_p$(4.5V): max = 38ns

74HCT688 Comparator

$t_{pHL}$ and $t_{pLH}$(4.5V): max = 34ns;

74HCT153 MUX

$t_{pHL}$ and $t_{pLH}$(4.5V): max **= **34ns

74HCT173 Reg

$t_{su}$(4.5) = 18ns

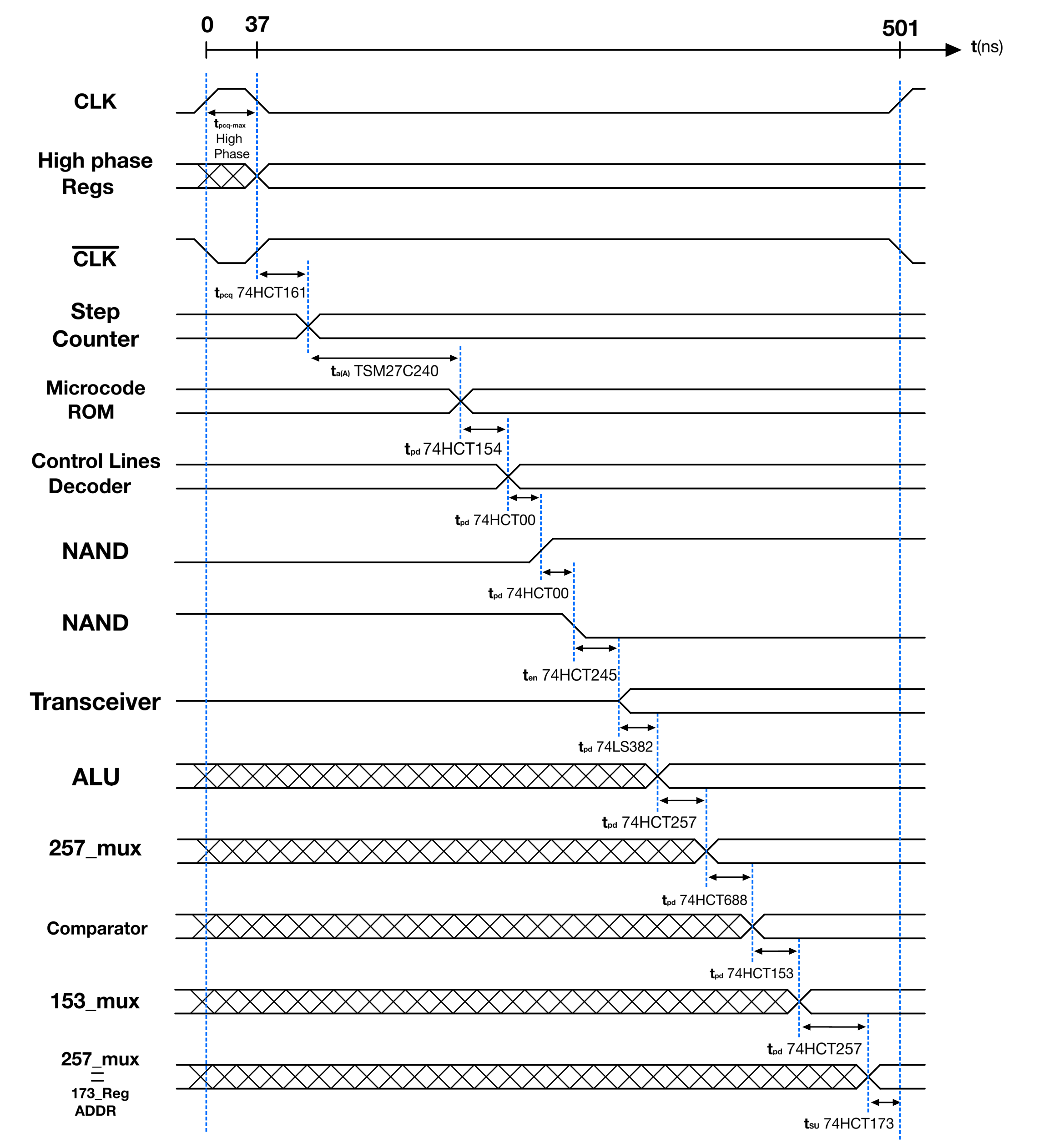

161 = 39ns

+

ROM = 120ns

+

154 = 35ns

+

NAND = 23ns

+

NAND = 23ns

+

ten_245 = 32ns

+

ALU = 30ns

+

257 = 38ns

+

ZER = 34ns

+

153 = 34ns

+

257 = 38ns

+

173 = 18ns

------------------

tpd LOW phase = 464ns

Therefore $t_{pd}(LOW) = \textbf{464ns}$

$t_{pd} = t_{pcq}(HIGH) + t_{pd}(LOW) = 37ns + 464ns = \textbf{501ns}$

By considering only the maximum timing values, the combined propagation delay for the critical paths of both the LOW and HIGH phases amounts to 501ns. Therefore, to ensure safe operation, the chosen clock frequency should accommodate this cumulative delay:

$f_\text{CLK_optimal} = 1 / {501 × 10^{-9}s} = 1.996\text{ MHZ}$

Duty Cycle = $100 × 37/501 = 7.385\%$

Implementation

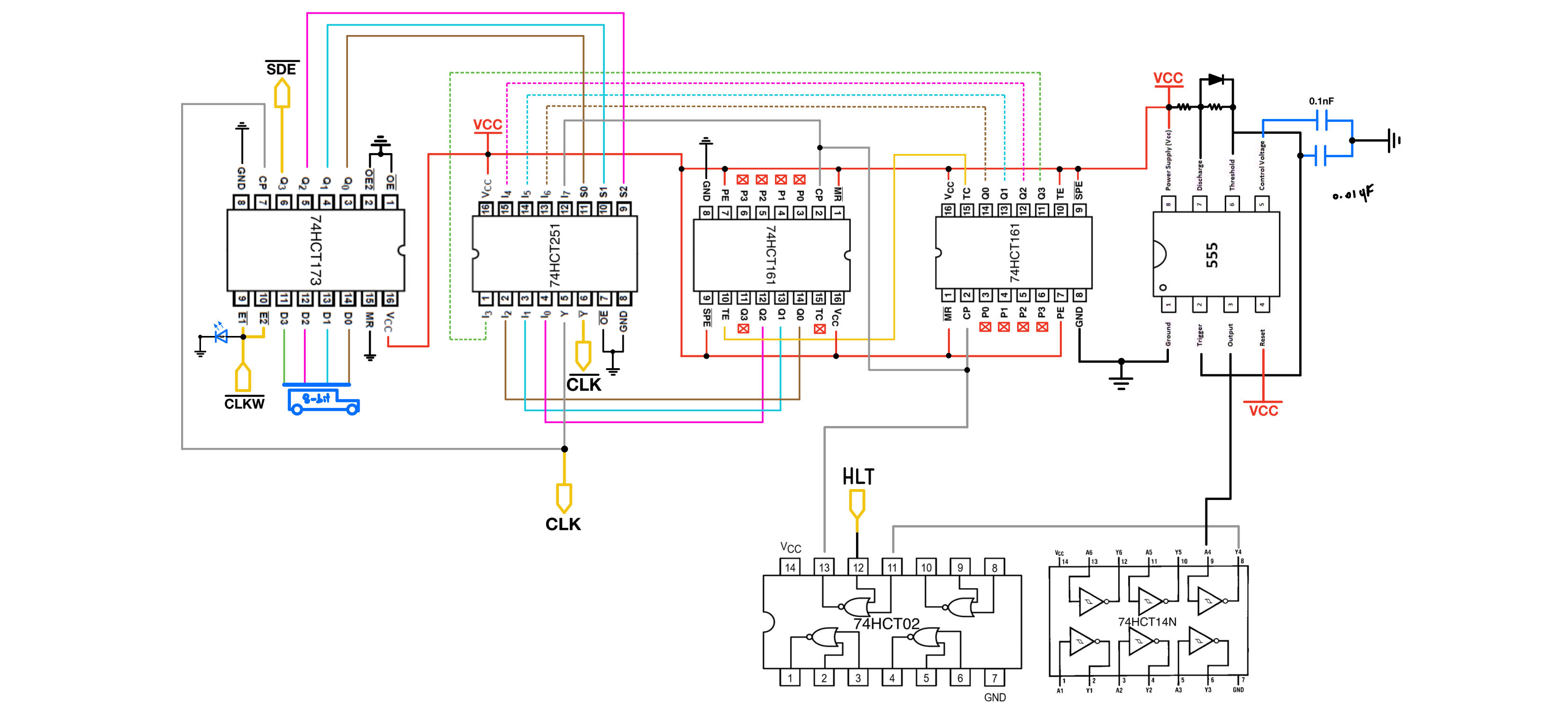

Control lines involved:

- |← HLT Halt

- |→ CLK Clock Signal

- |← ~CLW Clock speed select

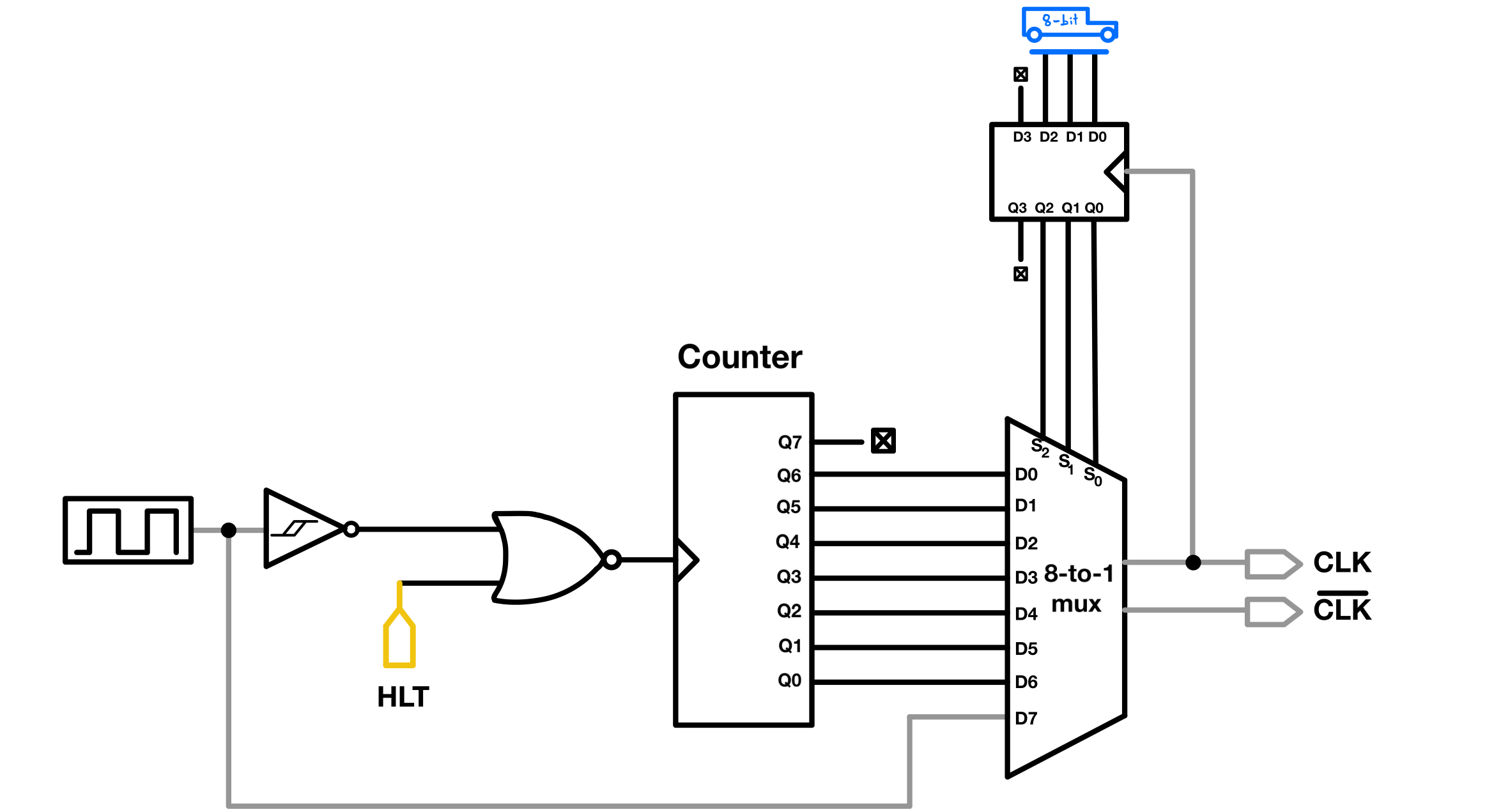

The main clock is generated by a 555 timer and then passed through an 8-bit counter (Made with two 4-bit counters). This counter essentially divides the clock frequency by two at each subsequent output, resulting in output signals that are successive halves of the original clock frequency. These outputs are then routed to an 8-to-1 mux. The mux, conveniently enough provides both a regular and an inverted output, which serve as the CPU’s HIGH phase and step counter clocks respectively. The mux’s select lines are controlled by a 4-bit register that’s connected to the data bus(The MSB of this register is used to control whether the segmented display should be ON or OFF).

Given that the counter begins by dividing the clock frequency by two, I’ve directly connected the original clock signal from the 555 timer to the MSB of the mux. The remaining seven inputs of the mux are connected from the seven most significant bits of the counter.

Note: I opted for a NOR gate and an inverter in this module, due to the convenience of integrating it with an available NOR IC I had already used to make a flip-flop on the breadboard located directly beneath the clock module. The choice of a Schmitt trigger inverter was primarily because I didn’t have any standard HCT04 NOT IC available; in fact, all the inverters in my build are Schmitt trigger inverters. While the Schmitt trigger can help mitigate potential noise from the 555 timer, it’s worth noting that a regular NOT gate would have worked just fine.

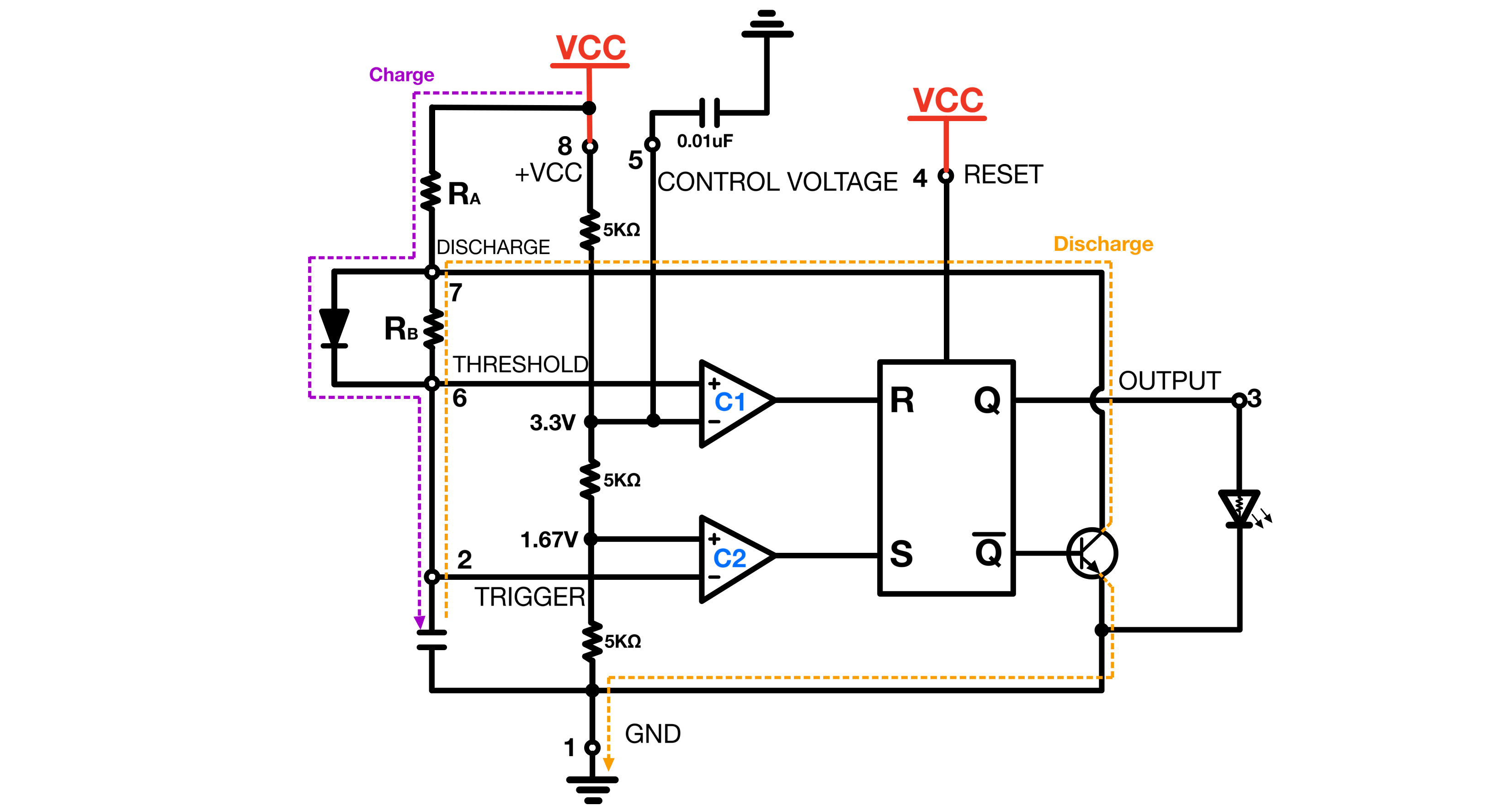

The permanent clock’s timer configuration is very similar to that of the astable debugging clock. The bypass diode simply allows the capacitor to charge only through ${R_A}$ and to discharge only through $R_B$.

With the bypass diode:

$t_\text{charge} = 0.693 × R_AC$

$t_\text{discharge} = 0.693 × R_BC$

$f = 1.44/((R_A + R_B)C)$

Let’s $(R_A + R_B)$ be $R_t$

⇒ $1.996\text{ MHZ} = 1.44/(R_tC)$

⇒ $R_t = 1.44/(C × 1.996\text{ MHZ})$

⇒ $R_t = (7.214 × 10^{-7}s)/C$

Note: Given that capacitance and resistance are inversely proportional, for any given capacitance $C$; multiplying it by a factor of $n$ (resulting in $nC$) allows the total resistance to be divided by the same factor $n$.

For a 0.1nF capacitor:

⇒ $R_t = (0.72144 μs/0.1nF)$

⇒ $R_t = 7.214 KΩ$

Since the duty cycle is 7.385%, the charging and discharging resistances must be:

$R_\text{charge}$ = $7.214 \text{ KΩ} × 7.385/100 = 0.533\text{ KΩ}$

$R_\text{discharge}$ = $R_t - R_\text{charge} = 7.214\text{ KΩ} - 0.533\text{ KΩ} = 6.682\text{ KΩ}$

Overclocking

The clock frequency($1.9 \text{ MHz}$) found above is the maximum theoretical clock rate, for the most stable working conditions.

The 555 timer that I use has a maximum frequency of $3\text{ MHz}$. So I tried out higher clock rates to see up to what point the CPU could still hold up.

It turns out that the closer you get to the 555’s max frequency, the less accurate the provided formulas become. I’ve attempted MANY combinations of RA/RB and capacitors to get a clock rate close to 2.5MHz; and the lower the value of any single component(The capacitor or one of the two resistors); the more arbitrary the clock rate. I found that the diode used matters more than anything else.

After many trial and error attempts; I ended up with the following values:

$C = 47pf$

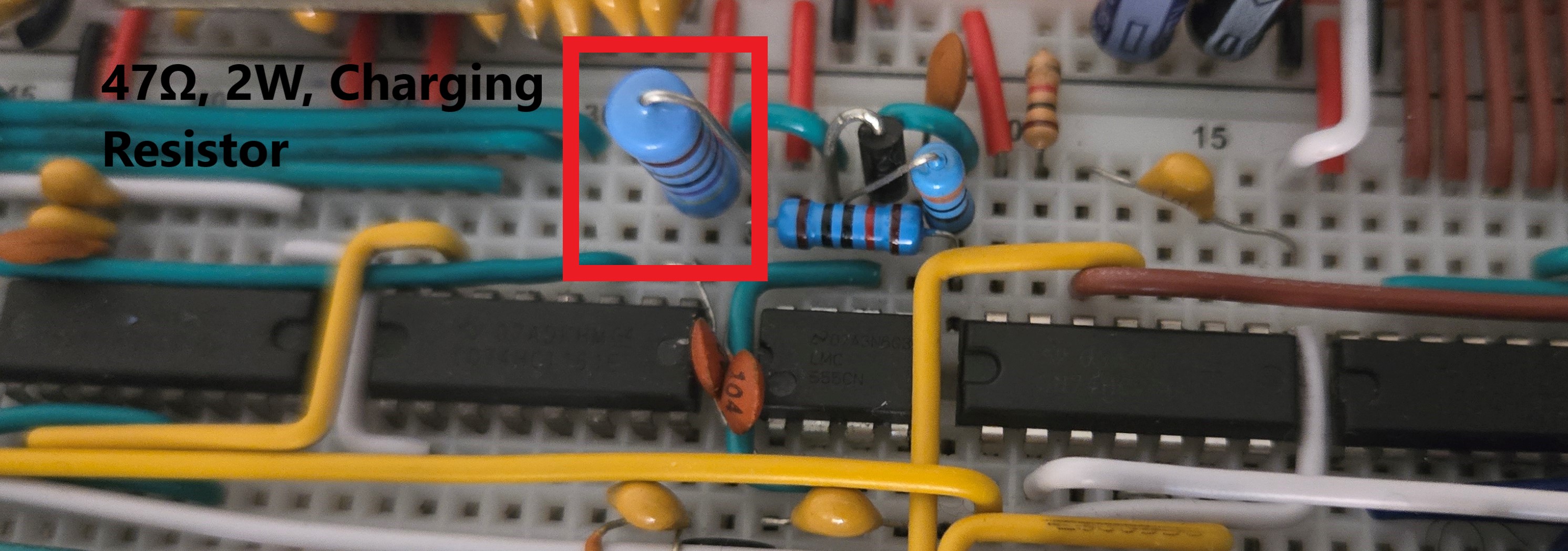

$R_A = 47\text{ Ω}\text{ Big 2-Watt resistor to avoid overheating due to the large current flow}$ $R_B = 2.481\text{ KΩ}(3.3\text{ KΩ} \text{ and } 10\text{ KΩ in parallel})$

With the values above, the clock rate should be higher than 10MHZ(which is impossible to reach using the 555) for an ideal diode. However, for whatever reasons, I get the following:

$f =2.2MHz$

$\text{Duty cycle = } 22\%$

So now I know for sure that the low phase can be as short as $346ns$; and since the high phase was found to be as short as $37ns$; a guaranteed stable overclocking can be set with $37ns$ high phase and $346ns$ low phase; resulting in a clock rate of $1/(37ns +346ns) = 2.6MHz$.

ICs

1x LMC555CN CMOS Single 555 Timer Low Power DIP-8 (Jameco, Datasheet)

1x 74HCT251 High-Speed CMOS Logic 8-Input Multiplexer (Digikey, Datasheet)

2x 74HCT161, Synchronous 4-Bit Binary Counter, (Digikey, Datasheet)

1x 74HCT173, 4-Bit D-type Registers with tri-state Outputs, (Digikey, Datasheet)

1x 74HCT14 Hex Schmitt-Trigger Inverters (Digikey, Datasheet)(Shared with Control Logic)

1x 74HCT02 Quadruple 2-Input Positive-NOR Gates (Digikey, Datasheet) (Shared with Control Logic)

«««««««««« Previous Post: Debugging Clock

Next Post: Bus & General Purpose Registers »»»»»»»»»»

Updated: