Numerical Display Module

Basics Primer

A BCD (Binary-Coded Decimal) decoder is a circuit that converts a binary-coded(binary equivalent) decimal number into a format that can be easily displayed or understood, usually for the purpose of display on segmented screens. In BCD, each digit of a decimal number is represented by its binary equivalent.

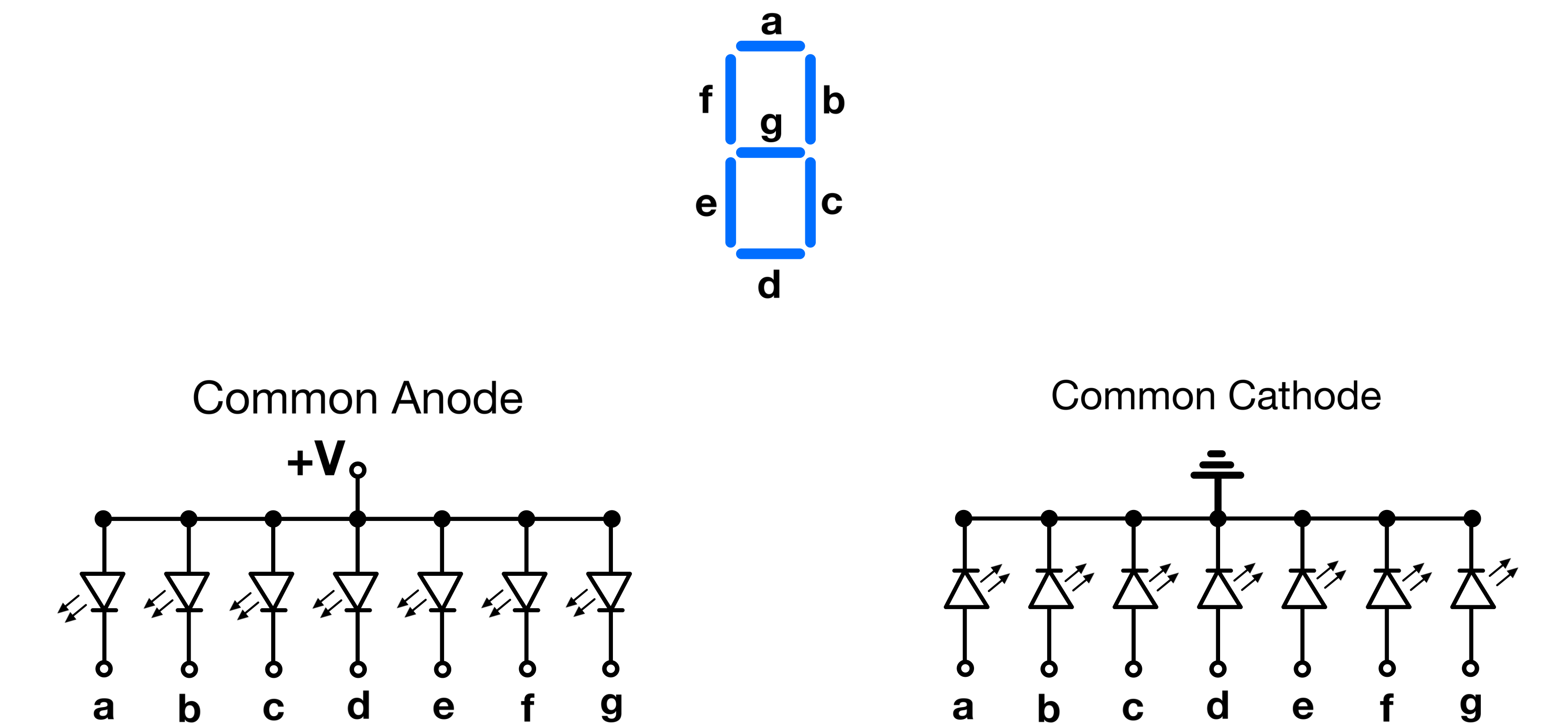

A segment(ed) display is a type of LED-based numerical display consisting of individual segments, each of which can be illuminated independently to form digits and characters. They usually come in two configurations:

Common Anode: All the anodes of the LED segments are connected together to a common positive voltage. Each segment is powered by grounding its cathode.

Common Cathode: All the cathodes of the LED segments are connected together to a common ground. Each segment is powered by applying a positive voltage to its anode.

The SAP-1 drives four 7-segment displays able to represent all decimal numbers fitting within 8 bits (0 to 255) as well as signed two’s complement(-128 to 127). My display module uses a set of six 14-segment displays that can cover all numbers fitting in 16 bits (0 to 65,535), including signed two’s complements (-32768 to 32767).

Why Choose a ROM?

Segmented displays can be driven in various ways. Below is an example of one of the simplest methods, in theory, though not the most straightforward in practice:

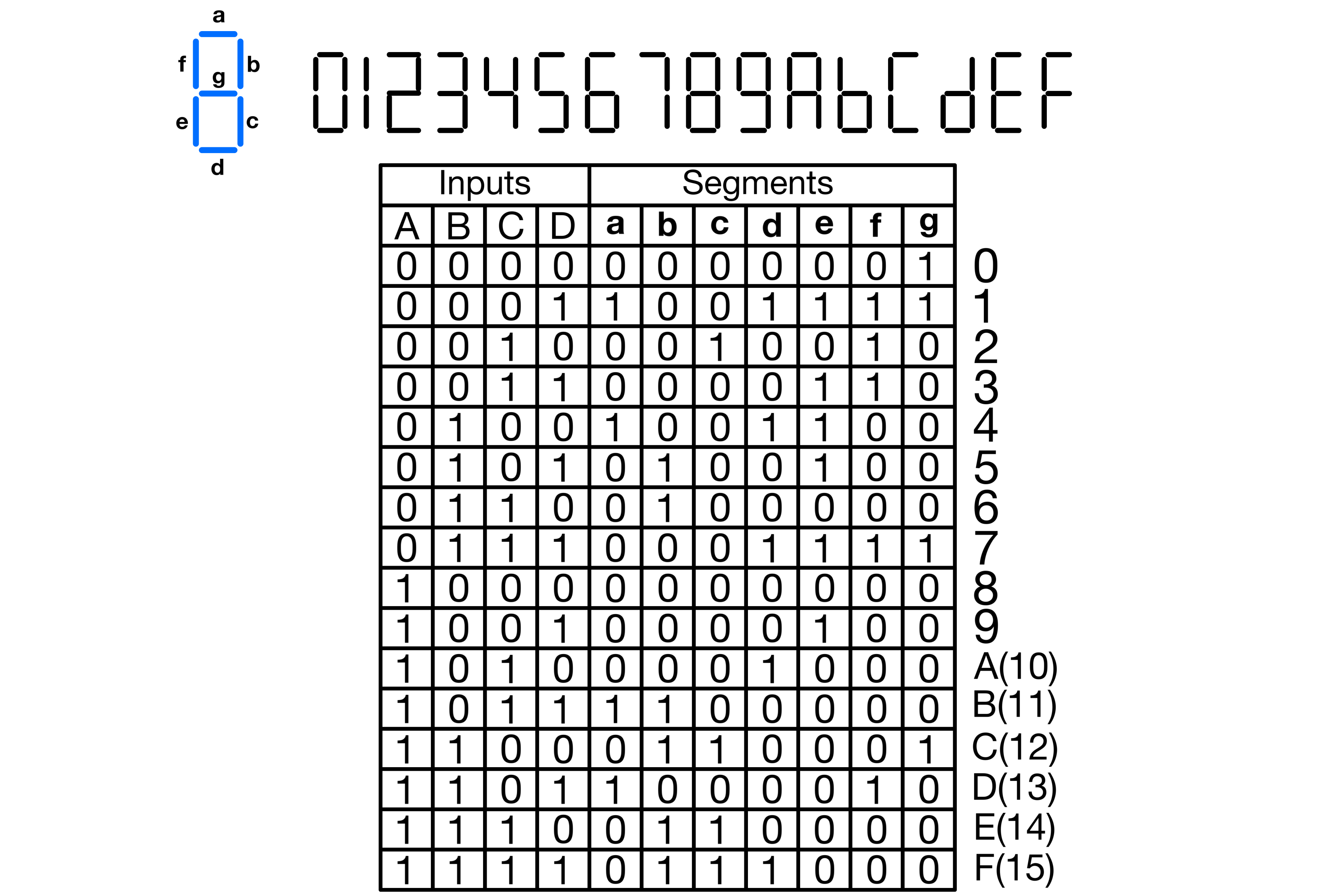

Given a 4-bit input, a seven-segment display can be used to show the hexadecimal representation of each of the input’s 16 possible values. Below is a truth table that outlines the required state for every segment of a common-anode seven-segment display to represent numbers from 0 to 15 in hexadecimal.

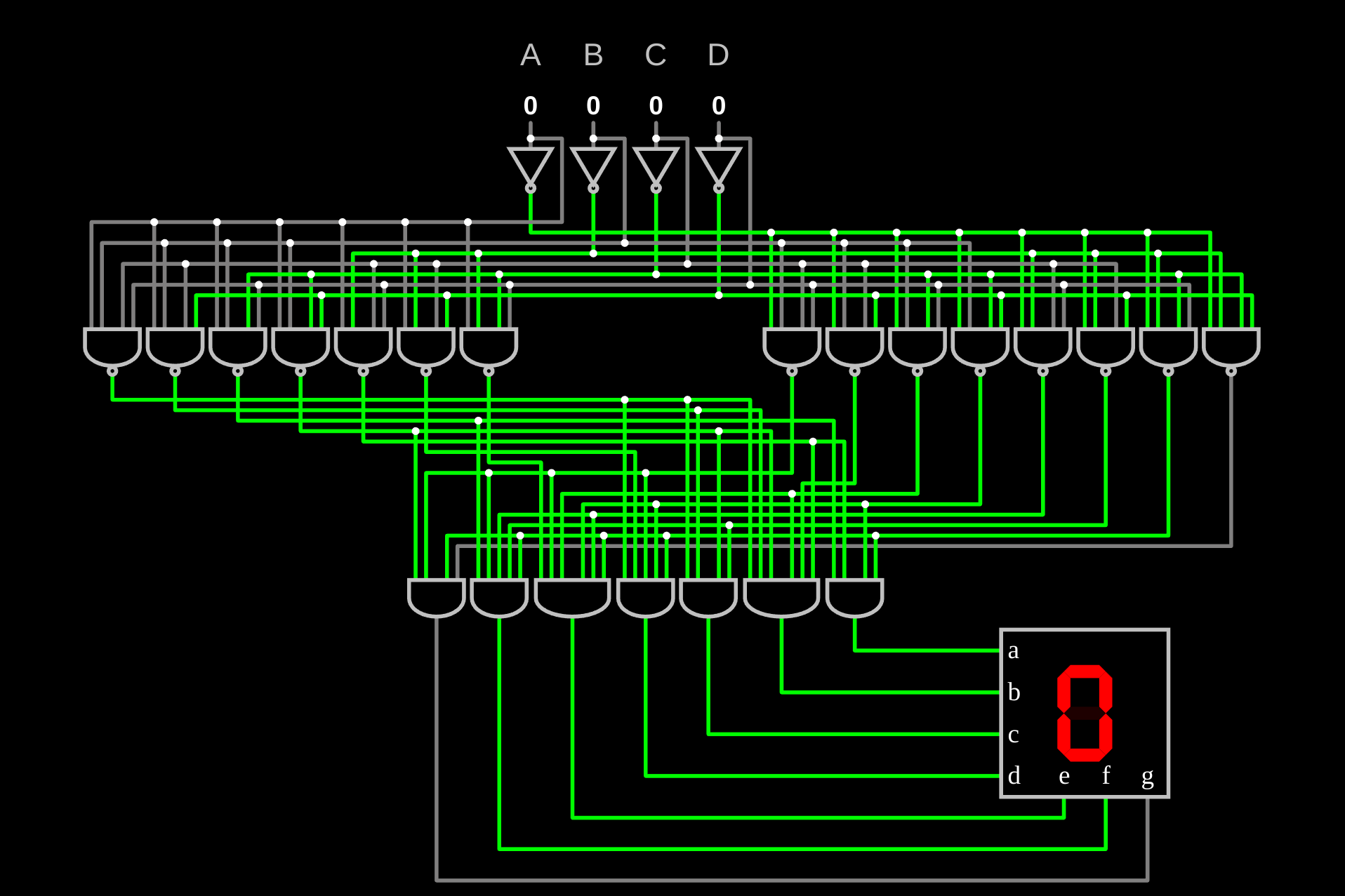

The picture below shows a circuit that implements the truth table. Note that beside the NOT gates, all the gates used in the implementation below are four-input gates, which means that regardless of how you’d want to implement this, if you only have two-input gates, you’d need a minimum of 3 gates per NAND and AND gate used in the figure.

Clearly, the number of gates required to implement the logic for all segments is substantial, even when using higher-input gates. A ROM chip, on the other hand, offers a more compact and cost-effective solution by storing the entire truth table for all segments. ROMs can emulate any combinational circuit by storing their truth tables, thereby serving as lookup tables. This approach replaces the need for a complex circuit dedicated solely to specific character outputs. It not only simplifies the circuit but also enhances adaptability and ease of programming for various display requirements.

Since the display module for the SAP-1 uses four 7-segment displays, a ROM with at least a 22-bit output(3 x 7 bits for the digit displays, and 1 bit for the sign display) can be used to drive all of them. Such a ROM would be relatively expensive, hard to find in through-hole and parallel format, and not easy to program without a dedicated PROM programmer. Another alternative could be the use of a combination of smaller-sized ROMs. For the four displays, four separate ROMs could be used to encode the value for each display individually.

Both of these methods are acceptable, considering their straightforwardness.

The SAP-1, however achieves this encoding with only one 16 Kbit (2Kb x8) Parallel EEPROM, with only 11 address pins and 8 output pins. Ben Eater’s display module by itself is to me a simple, but excellent example of electronic design ingenuity. Each display is activated sequentially, creating the illusion that all digits are displayed at the same time. This is achieved through a combination of a dedicated clock, a binary counter, and a decoder. The counter and decoder select which display is active and ensure the correct data from the EEPROM is shown, while the clock sets the rate at which each display is selected.

I made a Falstad circuit to visualize this process.

This is the highest frequency at which I could run the simulation with a decent recording render. This is just a replica, limited by lots of underlying code; the real circuit runs so fast that the switching rate cannot be perceived with the naked eyes.

This simulation follows the same logic as the SAP-1’s display module. The bottom left counter is for demo purposes; it is just there to cycle through all the values stored in the BCD ROM. On the actual module, the ROM is driven by the output register. The lower 8 address bits of the ROM are what selects the digit to be displayed, while the next 2 higher address bits are used to select which display the digit must be displayed on. The most significant address bit selects the encoding mode(Signed or Unsigned).

Note: As of April 1, 2023 (the day I made this simulation), Falstad did not support 14-segment displays nor ROMs with an input address size greater than 15 bits. For these reasons, I will refer to the 7-segment display demo mentioned above when describing my version.

Implementation

Control lines involved(4):

- |← ~SE Segmented display enable: Turn ON the display.

- |← SdW Segmented display write: Loads the two 16-bit output register.

- |← SdT Segmented display: Loads the 8-bit output temporary register.

- |← SdM Segmented display Mode: Signed or unsigned.

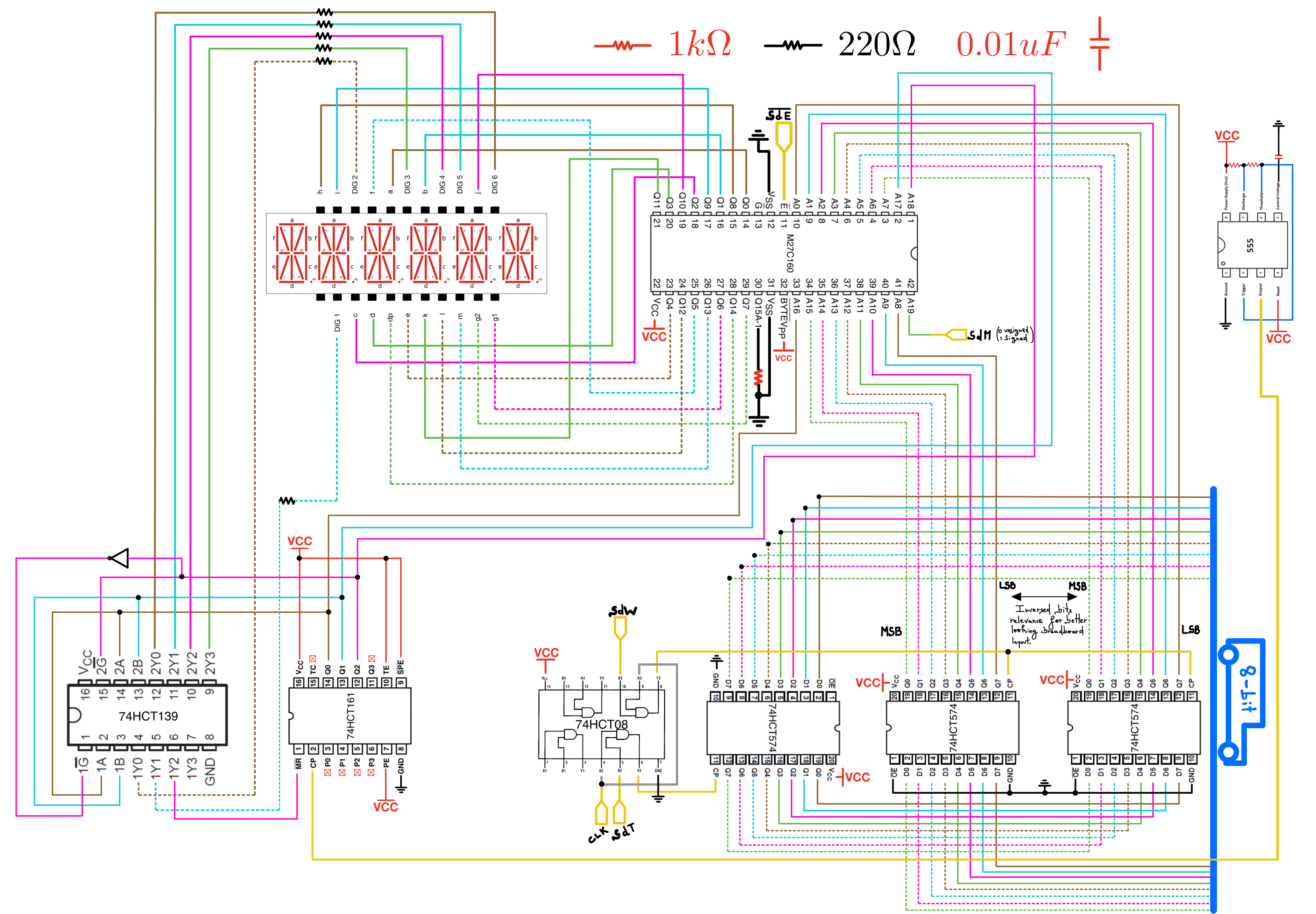

My BCD ROM is an M27C160 16 Mbit (1 Mb x 16) UV EPROM. It has 20 address lines (A0 to A19) and 16 data lines (Q0 to Q15). Emulative of the SAP-1’s display ROM, the lower 16 address bits (A0 to A16 ) of my BCD ROM are what selects the digit to be displayed, while the next 3 higher address bits are used to select which display the digit must be displayed on. The most significant address bit selects the encoding mode(Unsigned or signed two’s complements).

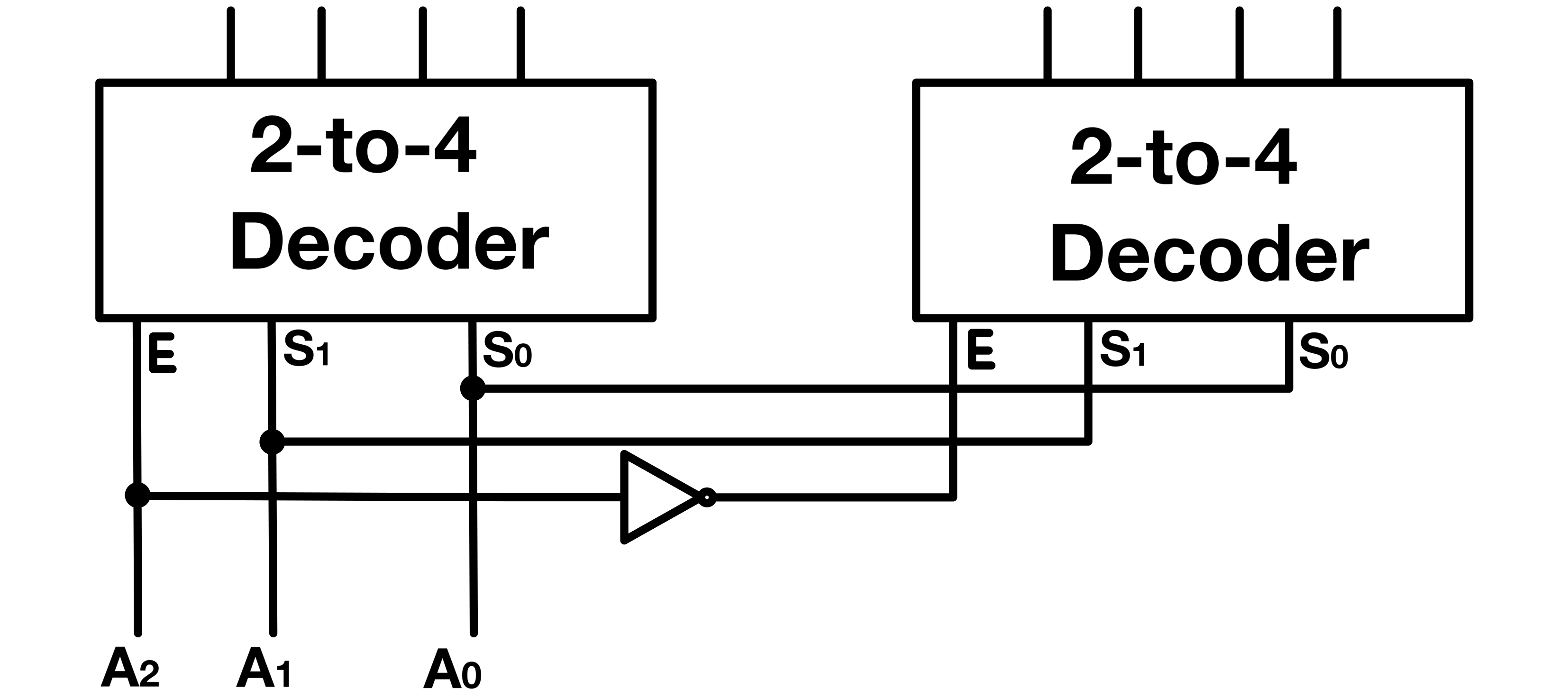

I did not have any 3-to-8 decoder at the time of making the display module, so I used the 74HCT139 Dual 2-Line To 4-Line Decoders to make a 3-to-8 decoder. Note that since I only have six displays, I only need 6 out of the 8 output lines of the decoder, therefore I tied the seventh output lines to the reset pin of the counter so that as soon as the display shows the last digit, no time is wasted on the the unused 7th and 8th output of the decoder, and the counter points right back to the first digit’s display.

Output Register

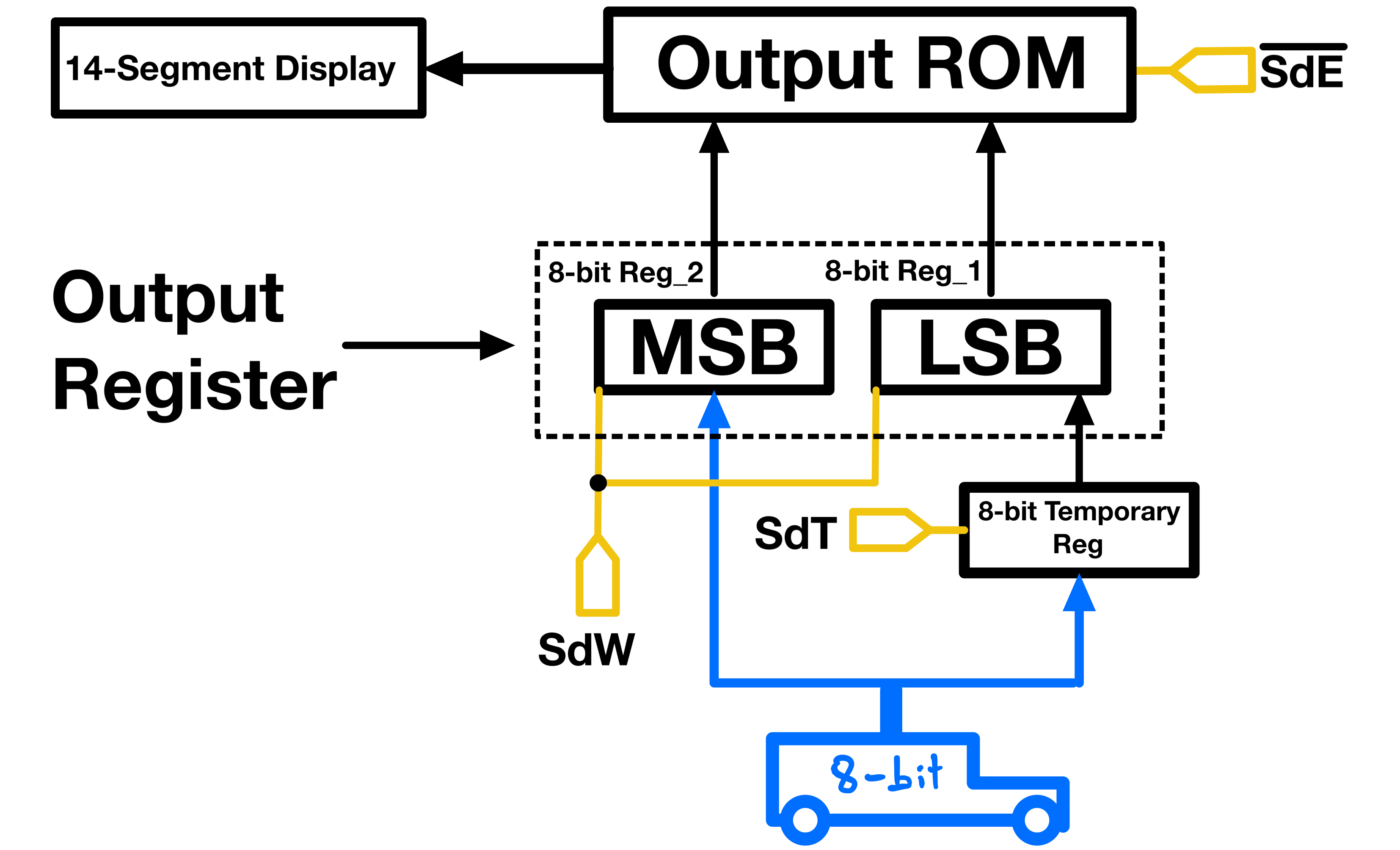

Since my display ROM supports 16-bit numbers, the driving register naturally has to be able to output 16-bit values. The output register however gets its input from the 8-bit data bus. I use a 16-bit register(made with to 8-bit registers), which is loaded in two cycles from a temporary register, and the data bus.

The reason I use three registers(16-bit reg + temp reg) instead of two(just the 16-bit reg) is to keep whatever value being displayed unchanged even through transitions.

The output register (Reg_1 and Reg_2) is always outputting to the ROM. In other words its “output enable” is always active.

Assume the display is currently displaying 00000 (0000000000000000), meaning Reg_1 and Reg_2 are holding 00000000 each.

Now let’s say I want to display 65534 (1111111111111111); meaning Reg_1 and Reg_2 must both be loaded with 11111111.

With no temporary register, first Reg_1 would be loaded with 11111111, a that point, the display would show 00255, because Reg_2 is still holding 00000000; which also means that the output register currently contains 0000000011111111. It is not until at least one additional cycle that Reg_2 would be loaded with 11111111, completing the whole value.

With the temp reg, first it would be loading it with 11111111, at which point the 00000 on the display wouldn’t change. Then when loading Reg_2 with 11111111 Reg_1’s load signal is simultaneously activated so that it reads the 11111111 already stored in the temp reg. This way the display does not show unrelated transitional values when changing the content of the output register.

BCD CODE

Below is a breakdown of the ROM organization and a Python code generating it:

Import array

I’ve experimented with a couple of binary handling libraries to generate ROM images using Python, and I find the “array” module to be the simplest to use.

# Segment patterns for digits on a 14-segment display.

# Modified the patterns for digits 0, 1, and 5.

digits = [0x3f, 0x6, 0xdb, 0x8f, 0xe6, 0xed, 0xfd, 0x7, 0xff, 0xef]

Note: I have a GitHub repository with code and a guide to generate digits and character patterns(ROM outputs) for different types of segmented displays.

# Opening/Creating the output file in binary mode to save ROM's image.

doc = open('rom1.bin', 'wb')

# Constants for the ROM's output mode and the ROM size.

OUTPUT_WORD_SIZE = 16

ROM_SIZE = 2**OUTPUT_WORD_SIZE

# Number of digits used, excluding sign digit.

DISPLAY_DIGITS = 5

# Deducting the number of unused states.

DECODER_SELECTS = 3

UNUSED_STATES = 2**DECODER_SELECTS - (DISPLAY_DIGITS + 1)

# Start address for unsigned numbers.

UNSIGNED_START = 0

# Start and end addresses for the sign of unsigned numbers.

UNSIGNED_0_START = UNSIGNED_END = ROM_SIZE*DISPLAY_DIGITS

UNSIGNED_0_END = UNSIGNED_0_START + ROM_SIZE

# Calculates the size to fill unused addresses with zeros.

FILL = ROM_SIZE*UNUSED_STATES

# Start and end addresses for the complements of numbers.

COMPLEMENT_START = UNSIGNED_0_END + FILL

COMPLEMENTS_SIGN_START = COMPLEMENT_END = COMPLEMENT_START + (ROM_SIZE*DISPLAY_DIGITS)

COMPLEMENTS_SIGN_END = COMPLEMENTS_SIGN_START + ROM_SIZE

ROM Organization

1- Addresses 0 to 393216 (First Half):

This half of the ROM is divided into six sections, each corresponding to one of the six displays. Each section has 65536 addresses:

1’s place, from 0 to 65536 10’s place, from 65536 to 131072 100’s place, from 131072 to 196608 1000’s place, from 196608 to 262144 10000’s place, from 262144 to 327680 Signs place, from 327680 to 393216,

The signs place is the 6th tick of the counter(6 * 65,536 = 393,216).

Note:

"H"inwrite(array.array("H", []))stands for unsigned short integers (Usually 2 bytes in most systems). It specifies the type of data that the array will hold.# Writes data for unsigned numbers. for i, index in enumerate(range(UNSIGNED_START, UNSIGNED_END, ROM_SIZE)): print(f"{10**i}'s place, from {index:,} to {index+ROM_SIZE:,}") for x in range(ROM_SIZE): doc.write(array.array("H", [ (digits[x % 10] if i==0 else digits[\ int(x / (10**i))% 10])] ))The data in these sections represents unsigned numbers, with each section corresponding to a different place value in a decimal number (units, tens, hundreds, etc.).

# Writes data for the sign place of unsigned numbers. print(f"signs place, from {UNSIGNED_0_START:,} to {UNSIGNED_0_END:,}\n") for x in range(ROM_SIZE): doc.write(array.array("H", [0x0]))

2- Addresses 393216 to 458,752 to 524288 (Middle Section):

This area is unused and filled with zeros. It acts as a buffer zone between the sections for unsigned numbers and their complements.

# Fill unused addresses with zeros. print(f"Filling {UNSIGNED_0_END:,} to {UNSIGNED_0_END + FILL:,}\ (unused addresses) with zeros\n") for x in range(FILL): doc.write(array.array("H", [0x0]))

3- Addresses 524288 to 917504 (Second Half):

This section is also divided into six segments, each with 65536 addresses.

# Writes data for the complements of numbers. for i, index in enumerate(range(COMPLEMENT_START, COMPLEMENT_END, ROM_SIZE)): print(f"Complements {10**i}'s place, from {index:,} to {index+ROM_SIZE:,}") for x in range(-(int(ROM_SIZE/2)), (int(ROM_SIZE/2))): doc.write(array.array("H", [ (digits[abs(int(x/(10**i))) % 10]) ]))These segments store the complements of the numbers. The data represents the negative values of the corresponding positive values in the first half. The two complements digits are activated using a switch connected to pin A19.

# Writes data for the sign place of complements. print(f"Complements signs place, from {COMPLEMENTS_SIGN_START:,} to \ {COMPLEMENTS_SIGN_END:,}") for x in range(-(int(ROM_SIZE/2)), (int(ROM_SIZE/2))): if x < 0: doc.write(array.array("H", [0xc0])) else: doc.write(array.array("H", [0x0]))Just like in the first half, each segment represents a different place value.

4- Addresses 917504 to 1048576 (End Section):

This final section, like the middle one, is unused and filled with zeros. It fills the remainder of the ROM, ensuring the EEPROM image (bin file) size is the same as the EEPROM’s actual size.

# Fills remaining unused addresses with zeros. print(f"Filling {COMPLEMENTS_SIGN_END:,} to {COMPLEMENTS_SIGN_END + FILL:,}\ (unused addresses) with zeros\n") for x in range(FILL): doc.write(array.array("H", [0x0])) doc.close()This code is also available on my GitHub.

ICs

1x M27C160-100F1 27C160 16MBIT UV EPROM(Datasheet)

1x LMC555CN CMOS Single 555 Timer Low Power (Jameco, Datasheet)

1x 74HCT161, Synchronous 4-Bit Binary Counter, (Digikey, Datasheet)

2x74HCT245, Octal Bus Transceivers With 3-State Outputs, (Digikey, Datasheet)

1x Common-Cathode 6-digits 14-segment display, (Alibaba)

1x Dual 2-Line To 4-Line Decoders/Demultiplexers (Digikey, Datasheet)

«««««««««« Previous Post: EPROM Programmer

Next Post: Program Counter and Stack Pointer »»»»»»»»»»

Updated: